The Unseeing

Even the things you think you know.’

After Sarah petitions for mercy, Edmund Fleetwood is appointed to investigate and consider whether justice has been done. Idealistic, but struggling with his own demons, Edmund is determined to seek out the truth. Yet Sarah, despite protesting her innocence, refuses to add anything to the evidence given in court: the evidence which convicted her. Edmund knows she’s hiding something, but needs to discover just why she’s maintaining her silence. For how can it be that someone would willingly go to their own death?

Q & A

What drew you to this period in particular?

How did you approach the borderline between known fact (whatever that is) and your fiction?

Did you find the fictional characters easier to work with than the 'factual' ones?

How did you endeavour to anchor your characters in your era, to make them truly historical and not simply twenty-first century people in period costume (which you did very well)?

Tell us about your research? Have you got any particular tips for someone else venturing into the very early Victorian era?

Lee Jasper runs the wonderful Victorian London site (http://www.victorianlondon.org), and Forgotten Books (http://www.forgottenbooks.com) do a great line in out of print nineteenth century texts. I also used Google books search, restricting my search to nineteenth century, to check particular facts.

Judith Flanders’ books on the Victorian era are great, as is Jerry White’s London In The Nineteenth Century: A Human Awful Wonder of God.

Are there any recognisable places or landmarks that feature in the novel?

Newgate prison, where both Gale and Greenacre were imprisoned, was demolished in 1904. The Old Bailey of course still exists, but in a very different form to how it appeared in 1837. People are no longer led through Dead Man’s Walk to be hanged, although the passage itself is still there.

How did you fit writing around your day job? Now that you’ve given up the day job, is book two proving easier?

Reviews

“This sizzling first novel was inspired by the Edgware Road Murder, a sensation of 1837. The author is a criminal justice solicitor, and she uses her knowledge of the law with great skill, but the characters, cleverly and sympathetically imagined, are the engine of the story.”

Kate Saunders, The Times

“A twisting tale of family secrets and unacknowledged desires. Intricately plotted and extremely convincing in its evocation of the everyday realities of 1830s London, this is a fine first novel.”

The Sunday Times

“I can’t remember the last time a book gave me such pure, unalloyed pleasure.I can’t imagine reading another new novel, and certainly not a debut, as thrilling and moving as this one for the rest of 2016.

The Irish Independent

“[An] accomplished debut: Mazzola quickly draws the reader in to this intriguing mystery. Mazzola skilfully conjures up a bygone world. If you like historical fiction then you’ll love this compelling murder mystery.”

The Daily Express

“Set in a vividly-imagined Victorian London, from the seamy horrors of Newgate Gaol to the bloated inns of court, this is a wonderful combination of a thrilling mystery and a perfectly depicted period piece. A brilliant debut.”

Deirdre O’Brien, The Sunday Mirror

“A compelling did she/didn’t she that’s full of the sights and sounds of Victorian England, this is a winner.”

The Sun

“This engrossing debut novel dramatically investigates a true murder case. The Unseeing engulfs you in a heady, addictive fog from the very start.”

Grazia

“[an] expertly crafted novel crammed with authentic descriptions and characters, and with a fascinating and compulsive plot, this is a thrilling debut.”

Heat

“Tragic, terrifying and authentic.”

Woman and Home

“The Unseeing is the debut novel of Anna Mazzola and you’d never guess it. This engrossing novel is thoroughly researched and beautifully written, presenting a dramatic interpretation of a true and infamous murder case.”

Kate Atherton: For Winter’s Night Book Blog

“With this intricately woven tale of trust, self-trust and deceit, Anna Mazzola brings a gritty realism to Victorian London. Beautifully written and cleverly plotted, this is a stunning debut, ranked amongst the best.”

Manda Scott

“Every now and then a debut novel comes along that stands out from the crowd. The Unseeing by Anna Mazzola is one…If you like your historical crime beautifully written, intelligent and genuinely moving, this is one for you.”

Katherine Clements (author of The Silvered Heart)

“Anna Mazzola’s Victorian crime novel has all the pace and drama of a psychological thriller. A book to be read voraciously; open-mouthed at the twists and turns. Who really murdered Hannah Brown? Why is the accused Sarah Gale so silent? Mazzola keeps the reader lurching from conviction to doubt over Sarah’s innocence. The twist at the end is utterly unpredictable, and the tension is ratcheted tight until the final pages. Historical crime fiction has a new star.”

Antonia Senior (author of Treason’s Daughter)

“A brilliantly researched, emotional, perceptive, and utterly engaging slice of Victorian crime fiction. Highly recommended.”

Raven Crime Reads

“I loved it, couldn’t put it down. As well as being a gripping, page-turning novel,The Unseeing immersed me in all the sights and sounds and smells of Victorian London, so that each time I put the book down I would look up surprised to find myself still in my own house in the twenty-first century.”

Claire Fuller (author of Our Endless Numbered Days)

“Whip-smart and crisp, I really enjoyed The Unseeing. Fine historical fiction.”

Kate Mayfield (author of The Undertaker’s Daughter)

“Had to finish The Unseeing this morning. A story of frailty, love & control, a plot to die for.”

Mary Chamberlain (author of The Dressmaker of Dachau)

“The Unseeing is deft, dark and delicious. Anna Mazzola writes brilliantly about Victorian London, a fascinating crime and an intriguing heroine. Her portrait of Sarah Gale is unforgettable, she has created a vivid and recognisable young woman who is of her time but speaks to ours.” JANET ELLIS (author of THE BUTCHER’S HOOK)

“Gripping plot and superbly vivid description of murderous Victorian history.”

SD Sykes (author of Plague Land)

“A sophisticated crime novel, page after alluring page. Anna Mazzola has brought to life a real life criminal case, no less prescient for today’s readers in its questioning of why we do the things we do. I urge you to read it.”

Dreda Say Michell (author of Blood Sister)

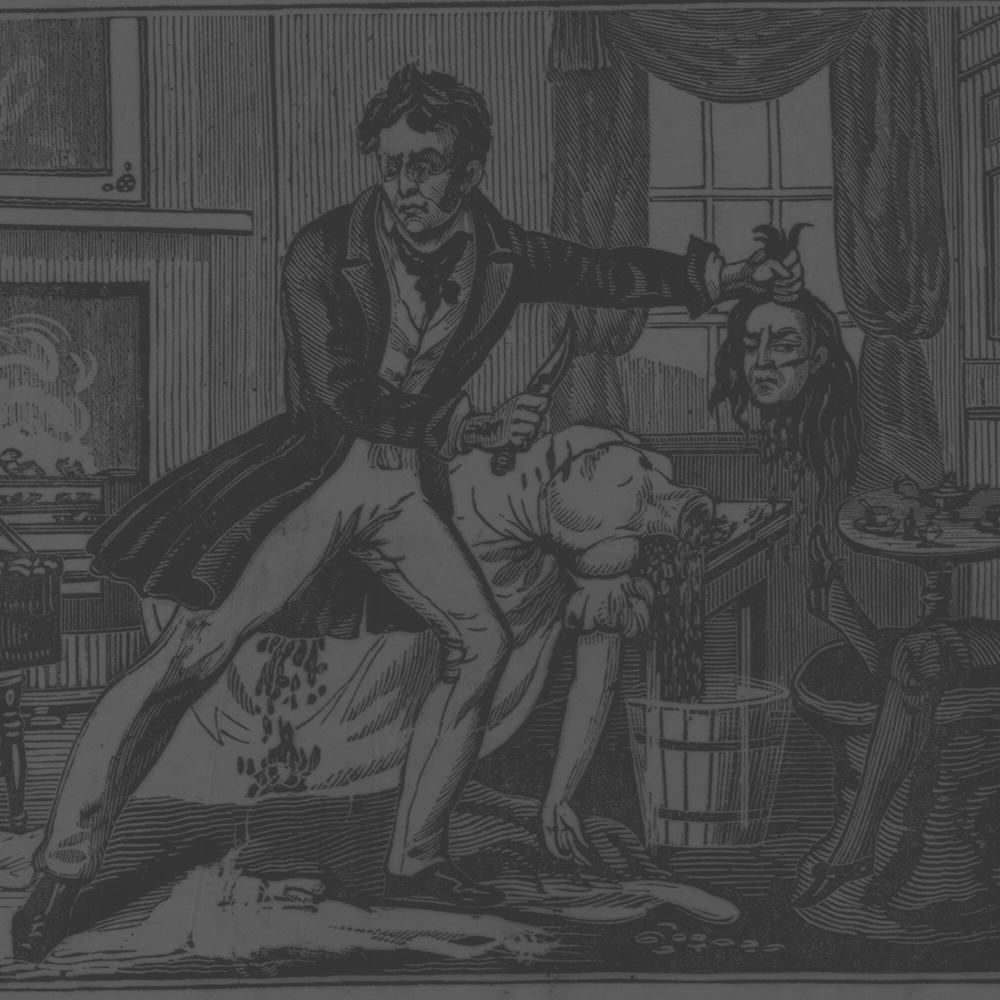

The Crime

When she was arrested, Sarah had in her possession several items said to belong to Hannah Brown, including two gold rings and some carnelian eardrops.

The Silence

At the trial at the Old Bailey, Sarah gave a short statement in which she said she was not at the house at the time the murder took place and knew nothing about it. That was disputed by the barristers for the Crown, who emphasized that that she had been surrounded by Hannah’s belongings, had pawn tickets for some of her clothes, and had borrowed water, supposedly to wash the blood from the floor. Sarah was said to have watched James Greenacre intently throughout the proceedings.

On 3 April 1837, Greenacre was convicted of Hannah’s Brown’s murder; Sarah of aiding and abetting him. The Spectator reported that Sarah seemed, ‘almost stupified’ at the verdict. She later, ‘threw her arms round Greenacre’s neck, and kissed him.’

The Prison

The prison was divided into three parts: the debtors’ side, the criminal side, and the woman’s side. By 1837, thanks largely to the work of social reformer Elizabeth Fry, conditions on the women’s side were far less squalid than they had been earlier in the century. However, prisoners were still cold, ill, and underfed, and many female prisoners had children with them, from babies to girls of 11 and 12.

Part of Newgate’s notoriety was connected to the fact that it was the place of public executions, a scaffold being erected outside the ‘debtor’s door’. Executions were moved inside the gaol in 1868, and the last execution took place in May 1902. In 1904 the prison was demolished.

Join my Readers' Club

Join my Readers Club to receive a FREE short story, plus news of giveaways, book recommendations, writing tips and more.

Contact me

Writers are lonely animals who love to hear from readers.

Write to me on anna@annamazzola.com and I’ll reply as soon as I can.

For events and publicity please contact Alex Layt at Orion Publishing.

My literary agent is Juliet Mushens at Mushens Entertainment.

Say hello on social media