A Dark and Dreadful Interest: Crime as Entertainment in the 19th century

We often think of the Victorians as a moralistic and upright bunch, and of the 19th century as a time when things became more civilized. After all, over the course of the century, violent sports were mostly outlawed, the Bloody Code was dismantled, and capital punishment was hidden from public view. Yet it was also the era in which crime reporting and murder as entertainment flourished. While researching for my début novel, The Unseeing, I discovered that our current fixation with true crime is nothing compared with what Dickens referred to as the Victorians’ ‘dark and dreadful interest’ in murderers and their punishment.

The Making of Murderers

Since the late 17th century, the Ordinaries of Newgate prison had been making a tidy profit from publishing the ‘confessions’ of condemned prisoners. However, the Ordinaries lost their monopoly when, in 1773, the keeper of Newgate began publishing the Newgate Calendar: ‘interesting memoirs of the most notorious characters who have been convicted of outrages on the laws.’

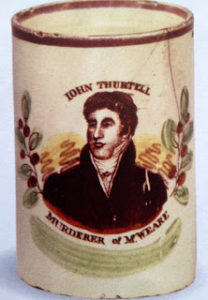

Sales, however, were still fairly small. It was with the expansion of the press in the early 19th century (aided by increasing literacy and the lowering and later abolition of stamp duty) that things really kicked off. As Judith Flanders explains in ‘The Invention of Murder’, several early cases were key in establishing the whole industry of death. John Thurtell, who in 1823 bludgeoned William Weare to death, became the subject of the first ‘trial by newspaper’. William Catnatch printed 500,000 copies of an account of the trial, the story was the lead item in the London Chronicle, Times, Morning Herald and Observer, two melodramas were written for London theatres (one before the case had even been tried), tourists arrived in droves for a tour of the murder scene, and balladeers made a killing selling songs based on the crime. 40,000 people turned out to see Thurtell executed, and the marketing of his story continued long after his death, as did his influence on the press.

The same grisly pattern was followed in the later cases of Maria Marten and the Red Barn (where Marten was murdered by William Corder), Burke and Hare (who sold the corpses of their 16 victims to an Edinburgh doctor for his anatomy lectures), and the Edgware Road murder: the crime for which James Greenacre and Sarah Gale were convicted, and the case on which The Unseeing is based.

Crime news was now prime news.

Broadsides and Penny Bloods

More affordable than newspapers were murder broadsides – printed sheets with an account of the crime, a woodcut illustration of the murder or execution, and often a lamentation. At the 1849 execution of Maria and Frederick Manning for the murder of her lover, 2.5 million broadsides were sold. However, sales for James Greenacre broadsides were slower. A street seller explained to Henry Mayhew that this was because Greenacre’s execution came close after Pegsworth’s (who had murdered a draper) and ‘that took the beauty off him. Two murderers together is no good to nobody’.

Cheap weekly papers were also being established and there was a booming industry in ‘Penny Bloods’ that originally concentrated on highwaymen and evil aristocrats, but later on true crimes, especially murders. And if there were no decent real-life crimes to draw upon, the penny bloods invented them. The most successful of all was a penny blood entitled The String of Pearls, which began publication in 1846. We know it now as Sweeney Todd, The Demon Barber.

The Blood-Stained Stage

It was not just the printing presses that ran on blood. Theatres (in particular, The Surrey and the Coburg) thrived on crime-based melodramas, to the extent that a commentator in 1840 noted of a Stepney theatre that, ‘the Newgate calendar and tales of terror stand in the same place as Homer did to the ancient dramatists.’

As Rosalind Crone explains in ‘Violent Victorians’, a host of bloody entertainments and representations saturated Victorian culture from the 1820s to the 1870s, including deeply violent Punch and Judy shows, and murderous peepshows: people would peer through the viewing-hole of a small box to see a painted murder scene in which the characters were pulled up and down by strings. The story of Maria Marten became a touring staple.

And then there was the greatest show of all: the gallows. Until 1868, felons were hanged outside Horsemonger Lane Gaol and outside the debtor’s door at Newgate prison, attracting enormous and excitable crowds of men, women and children. A huge number came to the hanging of James Greenacre, over a thousand waiting overnight outside Newgate to secure a place in the morning. Pie-men made their way through the throng selling Greenacre tarts while ballad-singers hawked the confession of the murderer: a fun day out for the whole family.

Scaffold Culture

If you couldn’t make it to the gallows, you could visit a moving waxworks display, many of which included relics of murderers or victims collected at the scenes of crime. Such shows ranged from the ‘respectable’ Madame Tussaud’s and her Separate Room (later the Chamber of Horrors) to itinerant waxworks displays, which travelled about between fairs.

You might also be able to purchase a memento: a splinter of wood from the Red Barn where William Corder killed Maria Marten, or perhaps a piece of the hedge through which her body had been dragged. Staffordshire pottery figurines of murderers and their victims were also available. Murderer John Thurtell’s face was crafted onto the side of mugs; the Red Barn murder was immortalised in figurines of Marten, Corder and also quaint models of the barn itself.

Also extremely popular were tours of the scene of the crime. After the murder of Hannah Brown, James Greenacre’s landlord gave guided tours of his house in Camberwell. These proved so popular that the police had to be brought in to stop visitors removing relics of the crime – tables, chairs, even the door.

The Common Attribute of Every Age

No such tours operate today, of course, but numerous guided walks continue to celebrate the most famous of Victorian murderers: Jack the Ripper. Our continuing fascination for violence and murder manifests itself in different ways: in the success of shows such as Serial, The Jinx and Making a Murderer, and in the prominence given to murders by the media. Rightly or wrongly, we continue to be enthralled by human tragedy – by what drives people to commit dreadful crimes, by what happens to the victims. ‘This appetite of the mind for particulars of great crimes and criminals has been stigmatized as vulgar,’ said the Daily Telegraph in 1881. ‘It is only vulgar in so far as it is universal, the common attribute of every age, people and clime.’

This post originally appeared on the History Girls blog.