Behind Bars: Writing Prisons

I’ve spent quite a bit of time in prison. Admittedly, not as an inmate, but as a solicitor visiting clients. My first training ‘seat’ was in the Home Office Prisons Team, defending cases brought by prisoners in person. Later, I left Government to bring claims against my former employer, often on behalf of victims, but sometimes for those wrongly detained or suffering abuse in institutions. Prisons are strange, fascinating and often brutish places full of some of the most damaged and vulnerable people in our society. They disclose a life very far removed from the conventional existence that most of us lead. Perhaps it’s not a huge surprise, then, that I ended up writing about a prison, albeit one that no longer exists.

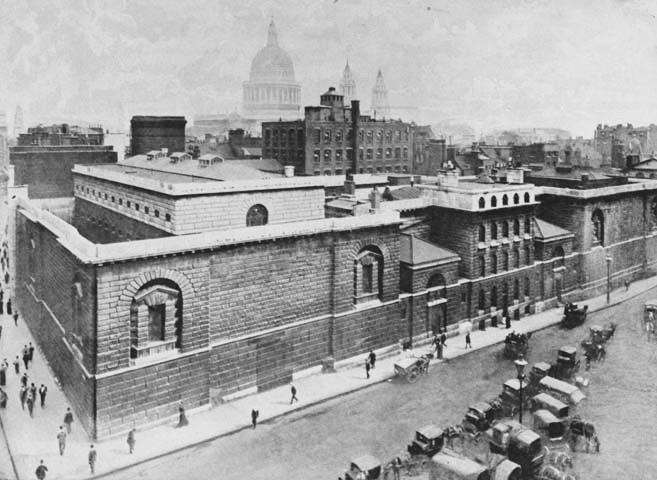

The Unseeing is based on the real life of woman called Sarah Gale who, in 1837, was convicted of aiding and abetting her lover, James Greenacre, in the murder of another woman. While Sarah’s petition for mercy was being investigated, she was detained in Newgate: the most notorious prison in London. The great stone fortress stood at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey and was the reason I held my book launch at the Magpie & Stump pub, where people would have stood at the windows to watch the hangings outside the Debtor’s Door. Over its seven-hundred year history, Newgate was extended and rebuilt many times. It was finally torn down in 1902.

How to get a feel for a place that no longer exists?

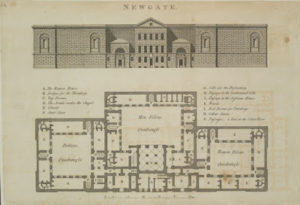

I read prison diaries and parliamentary commissions, I searched for sketches and pictures and studied plans of Newgate to get a sense of what that prison might have been like in the early 19th century. The short answer is: horrific. An 1835 Committee referred to Newgate as a ‘stain’ on the character of the City of London; an institution ‘which outrages the rights and feelings of humanity.’ The prison was divided into three parts: the debtors’ side, the criminal side, and the woman’s side. By 1837, thanks largely to the work of social reformer Elizabeth Fry, conditions on the women’s side were less squalid than they had been earlier in the century when people slept in straw and gaol fever was rife. However, prisoners were still cold, ill, and underfed, and many female prisoners had children with them, from newborn babies to girls of eleven and twelve, all living together with hardened criminals and the mentally ill.

I also read brilliant fiction set in prisons, institutions and concentration camps: Antonia Hodgson’s Devil in the Marshalsea, Andrew Hughes’ Convictions of John Delahunt, Alias Grace by Atwood, Affinity and Fingersmith by Sarah Waters, Gulag Archipelago, If This is a Man, The Last Day of a Condemned Man, Victor Hugo. And a lot of Dickens, who was fascinated by prisons and criminal justice in general, having witnessed as a child his father being imprisoned in the Marshalsea for debt. These books all work because they capture the horror of confinement: of what it must be like to be locked in a dark and dangerous place with little hope of escape.

I also used physical objects. Perhaps this is odd. I have a set of replica prison keys: a bizarre and wondrous gift from my mother, which have a reassuring and heavy clank. I spent some time with the door to Newgate, which is now in the Museum of London. I lingered in dark and enclosed places: a fortress in Portugal, a monk’s cell, a dungeon, to try and get a sense of what it must be like to be detained.

Of course, it might have helped to have actually got locked up. Jean Genet wrote his first novel, Our Lady of the Flowers, while in prison near Paris, scrawled on scraps of paper. Miguel de Cervantes drew his inspiration for Don Quixote from his time as a galley slave. The Marquis de Sade knocked out eleven novels, sixteen novellas and twenty plays during his eleven-year stint in the Bastille. I, however, have remained at liberty and therefore had to resort to the usual writers’ tool: imagination. I imagined the dark cells beneath Newgate where prisoners were manacled, punished and abandoned. I imagined the stench of unwashed close-packed bodies (although I did have Glastonbury festival to draw upon). I envisaged the gloom and desperation of Sarah’s prison cell with its spyhole through which she was watched.

Ultimately, Newgate Prison became quite real for me. I hope it does for the reader, although they may not thank me for it.

This piece originally appeared on Isabel Costello’s Literary Sofa.