Character motivation and agency in historical fiction

This is latest in a series of blog posts discussing how to write historical fiction and following how I wrote my latest historical novel, The House of Whispers.

Today I want to look at how to ensure your characters have agency. That’s often tricky in historical fiction, particularly for female characters who in their daily lives would have been highly circumscribed.

The Importance of Character

Character development is essential to all genres of fiction. Characters and their motivations and needs are what will propel the story forward. You can make the plot as twisty and action-packed as you like, but if the readers don’t care anything about the characters, it’s unlikely they’ll be gripped by what happens to them. None of this is new.

What is perhaps less talked about on creative writing courses and in ‘how to’ books is the importance of giving your characters agency. However, lack of agency is often cited by literary agents and editors when turning down manuscripts, so let’s look at how to make sure you have a winner!

What is Character Agency and Why does it Matter?

Agency is ‘the capacity, condition, or state of acting or of exerting power’. Character agency in fiction means a character’s ability to take action to affect the events of the story.

In order for a character to engage us and make us root for them, they have to have agency and to actively pursue what they want (or think they want). It essentially means ‘doing things’ and making decisions, rather than simply having things ‘happen’ to them. If your character doesn’t to some extent steer their own course, it doesn’t matter how realistic and multi-faceted you make them, or how much you think about their backstory. They’re likely to be considered ‘drippy’ or dull.

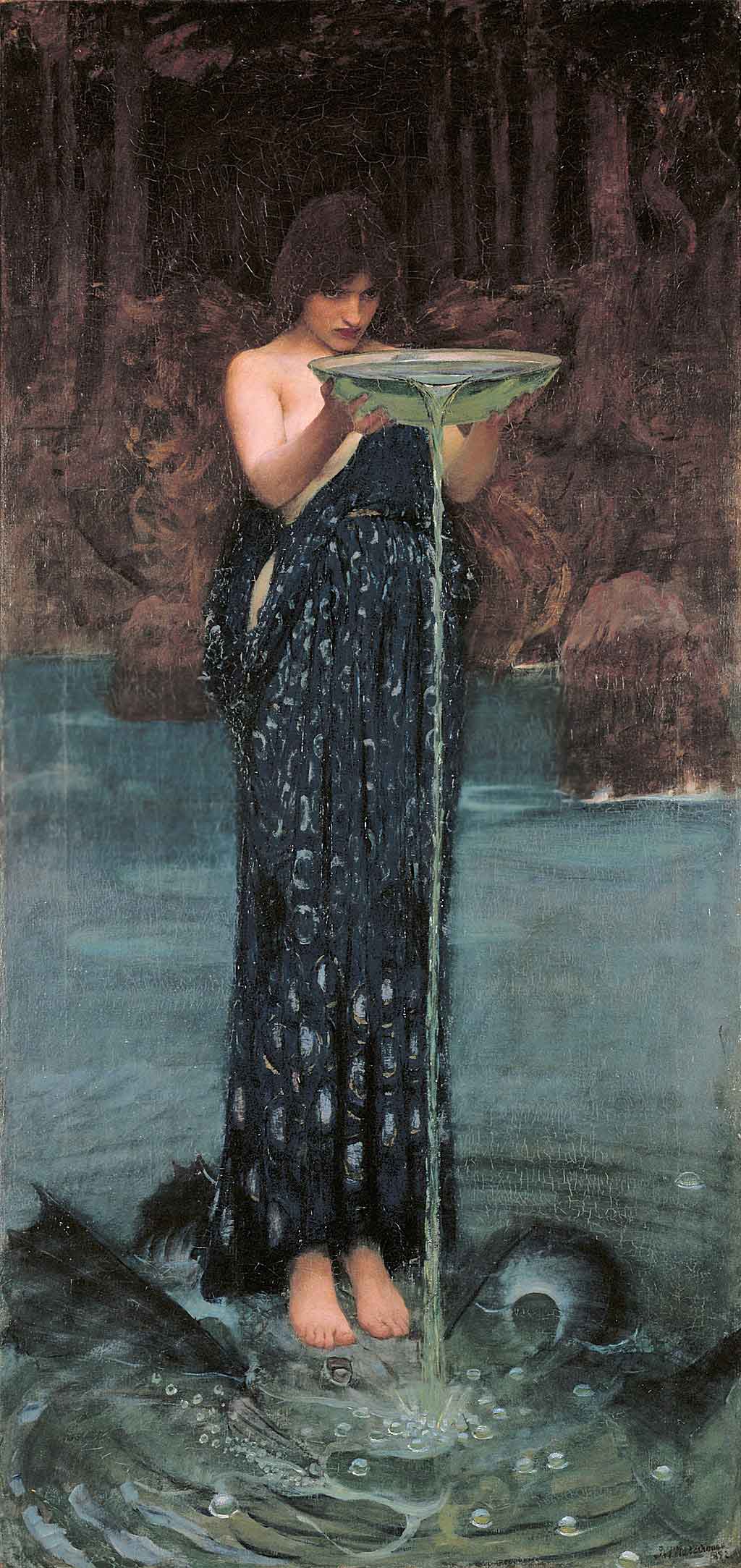

If, on the other hand, they attempt to steer their role in the story, they are far more likely to be considered interesting and powerful. Think of Madeleine Miller’s Circe, Agnes in Hamnet, Cora in The Underground Railroad, Scarlet O’Hara in Gone with the Wind.

Character Agency in Historical Fiction

Character agency can pose particular issues in historical fiction given that people in previous eras, particularly those who were marginalised, did not have as much freedom or ability to steer their own destiny as we do today (and of course people in some societies are still hugely restricted).

That complexity is heightened when creating female characters because, within the period of history about which you’re writing, women’s lives might well have been heavily circumscribed, with male family members making decisions as to who they should marry, and where and how they should live.

It also applies to other oppressed characters who may have had little control over what happened to them.

Common Problems

The main character will sometimes end up as largely a bystander or a witness to the main plot: a passenger rather than a driver of it. Or you may find that your character is too much a put-upon victim who never seeks opportunities to save themself. It may be that other characters drive the plot, or pass the essential information to the protagonist. If they’re an investigator, are they going out and seeking the evidence, rather than having it handed to them?

The ‘bystander’ problem arose for me during the first draft of my third novel, The Clockwork Girl. The main character is a prostitute called Madeleine who is put into the house of an automaton-maker as a chambermaid, and a police spy. I realised that she was mainly observing the action rather than directly driving it, so I had to rewrite the first section of the novel to make sure we were focussing on her story and what she wanted to achieve.

Character Motivation

The most important factor in ensuring your characters have agency is to give them a clear goal. Tell us what they want (what they they really really want). Is it to find love? Achieve self-acceptance? Get revenge? Find the killer? What your character thinks they want at the beginning of the novel might not actually be the thing they need to make them happy, but you still need to show the character striving to achieve some goal in order to propel them, and us, through the book.

Madeleine Miller gives Circe far more agency and power than we usually see in female characters in Classical mythology. She gives us a Circe who knows what she wants and knows she must be strong to survive:

‘’It is a common saying that women are delicate creatures, flowers, eggs, anything that may be crushed in a moment’s carelessness. If I had ever believed it, I no longer did.’

Circe realises that she must embrace her abilities and can in that way be powerful, even in exile: ‘I will not be like a bird bred in a cage, I thought, too dull to fly even when the door stands open.’

In my novel The House of Whispers, the main character, Eva, is a young woman lacking in confidence and in the ability to resist. Her arc over the course of the novel is from believing she is powerless to learning to fight back. In order to make sure she didn’t seem drippy at the beginning, I gave her a very strong desire to find acceptance and safety, and specifically a desire to become truly Italian and thus ‘safe’ within the Fascist state. That of course backfires terribly as the novel goes on, but she is at least driving the plot from the very beginning.

As well as the big goals, show us the smaller, more immediate ones. What is your character trying to achieve in every chapter, every scene? What action will they take to get it (even if they are thwarted)? What decisions do they make in pursuit of their aim? If you consider this, you can ensure that your character – by their choices and actions – is driving the momentum of the plot, rather than having things happen to them.

Show us the action

Even where characters are making decisions or taking action that effect the plot, where that happens offstage it will blunt the impact. Where you can, put the key action on the page: even if it’s a decision rather than an action, show us in internal monologue or dialogue why they are making that decision and what it means.

If your character is an investigator, show them striving to hunt down the clues rather than reporting them after the fact. None of us would have cared much about Matthew Shardlake’s adventures had other people just handed him all the evidence on a plate.

Showing agency in constricted circumstances

In your novel, particularly if you’re writing about an oppressed character, it may be that they cannot realistically escape the confines that have been set on them (e.g. they’re locked up, in an abusive marriage, kept under close guard by strict parents). However, that doesn’t mean they can’t direct elements of the story.

For example, in Fingersmith by Sarah Waters, both Sue and Maud appear to be constrained by their families and circumstances, but both woman subtly direct the plot, and, ultimately, their way out. Margaret Atwood’s Grace Marks in Alias Grace is in prison, she but manipulates the other characters – and the telling of her own story – to her advantage. In fact, Atwood is particularly excellent at character agency. You can look at any of her novels and find brilliant examples – Offred in Handmaid’s Tale, Iris in The Blind Assassin.

Even if a character can’t move the big pieces, they can still direct the action of smaller things. In Sarah Dunant’s stunning novels about the Borgias, Blood & Beauty and In the Name of the Family, Lucrezia Borgia is directed who to marry and how to behave, but she is very far from a passive character. We understand from the very beginning that this is a woman who knows her own mind and will achieve what she can, within the limits that are set.